Layers of Light

Eric Bowman brings drama to the light and shadow of the IWest in a new show at Maxwell Alexander Gallery.

By Michael Clawson

In a 1957 short film, Walt Disney stood in his office and held up a framed blueprint for what he called a “super cartoon camera.” Although it had been developed two decades earlier by Disney animators, this was one of the first times the public would get to see the creation: the multiplane camera. It was a beast of filmmaking equipment: a tall steel turret with gear-driven trays filling a center tower that could shuffle the trays up and down left and right on three axes of movement. Mounted on top, and pointing down into the steel battlement, was a camera—a literal eye in the sky.

The idea behind the camera was to separate a sequence of animation onto individual glass panes, each representing a different depth in the scene, from the moon at the furthest distance to nearby foliage in the immediate foreground. These glass panes would be laid on the trays and moved slightly between each picture, or frame, of the film. The movement, when sped up, would not only reveal animated motion, but three-dimensional depth.

For Oregon painter Eric Bowman, the multiplane camera seemed like a revelation at the time. “I remember seeing Disney employ the multiplane camera in the Bambi and Pinocchio movies. It offered a way to shoot several background paintings at once and then bring them into and out of focus to give you the effect that you were coming into a scene. I remember seeing it used and really admiring the way it created a sense of drama,” Bowman says, adding that his own work embraces similar principles of the multiplane camera, specifically how it layers images and builds drama through those layers. “When I look at my own work, I see the transition from the sky to the feet of the figure, the foreground shadow versus the background shadow, the way the lighting shifts and illuminates one cloud but then obscures another...creating these layers of light is a vehicle, a mechanism to create more interest in my paintings.”

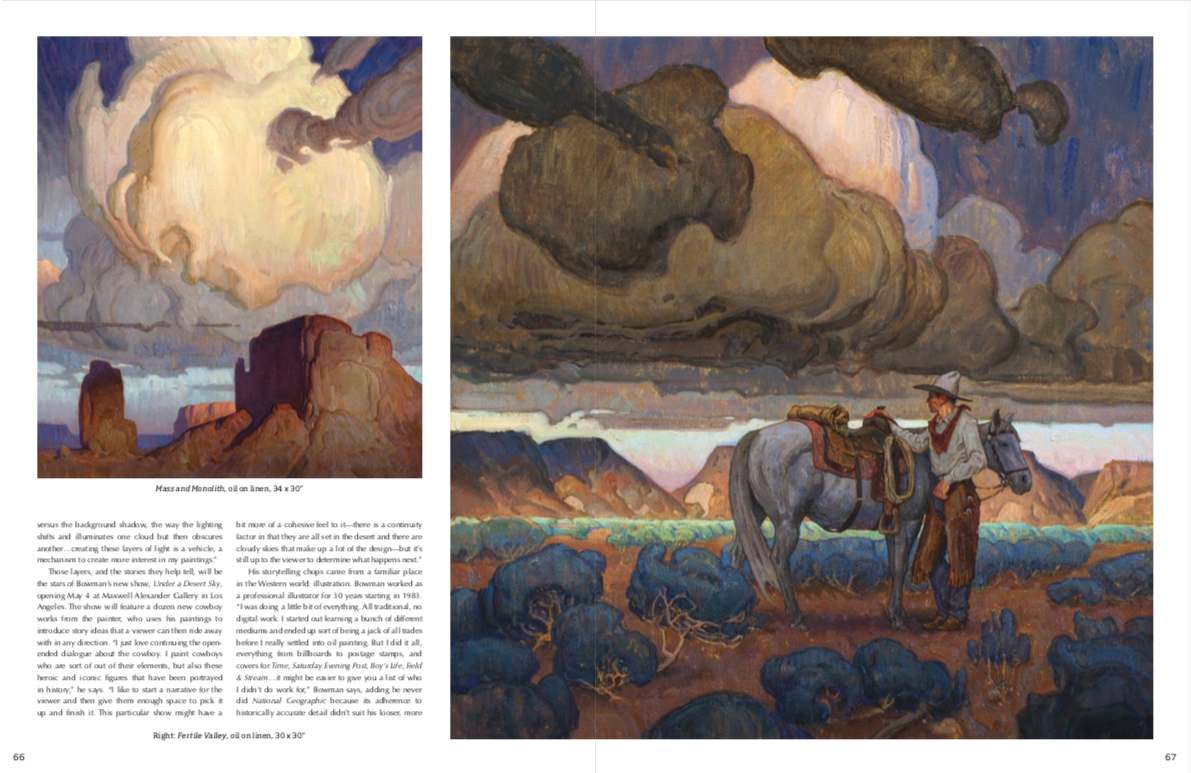

Those layers, and the stories they help tell, will be the stars of Bowman’s new show, Under a Desert Sky, opening May 4 at Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Los Angeles. The show will feature a dozen new cowboy works from the painter, who uses his paintings to introduce story ideas that a viewer can then ride away with in any direction. “I just love continuing the open- ended dialogue about the cowboy. I paint cowboys who are sort of out of their elements, but also these heroic and iconic figures that have been portrayed in history,” he says. “I like to start a narrative for the viewer and then give them enough space to pick it up and finish it. This particular show might have a bit more of a cohesive feel to it—there is a continuity factor in that they are all set in the desert and there are cloudy skies that make up a lot of the design—but it’s still up to the viewer to determine what happens next.”

His storytelling chops came from a familiar place in the Western world: illustration. Bowman worked as a professional illustrator for 30 years starting in 1983. “I was doing a little bit of everything. All traditional, no digital work. I started out learning a bunch of different mediums and ended up sort of being a jack of all trades before I really settled into oil painting. But I did it all, everything from billboards to postage stamps, and covers for Time, Saturday Evening Post, Boy’s Life, Field & Stream...it might be easier to give you a list of who I didn’t do work for,” Bowman says, adding he never did National Geographic because its adherence to historically accurate detail didn’t suit his looser, more narrative-driven brush. “The last dozen years I was an illustrator I was transitioning slowly to fine art painting. The storytelling, the book and magazine covers, the advertising work...it all taught me how to tell stories visually. I was doing it all the time, so naturally it came out very strongly in my fine art work.”

Of course, Western art has a rich history with illustrators, from way back with Frederic Remington, N.C. Wyeth and Philip R. Goodwin to more contemporary painters like C. Michael Dudash and Howard Terpning. Bowman’s work tends to dip back to the years of Wyeth and Goodwin, particularly to the 1920s and 1930s, when cowboys wore big Stetson hats and when both artwork and real cowboys were influenced by, or at the very least aware of, the Hollywood Western and its profound revolution on American culture. Cowboys had a bit of style back then, Bowman adds.

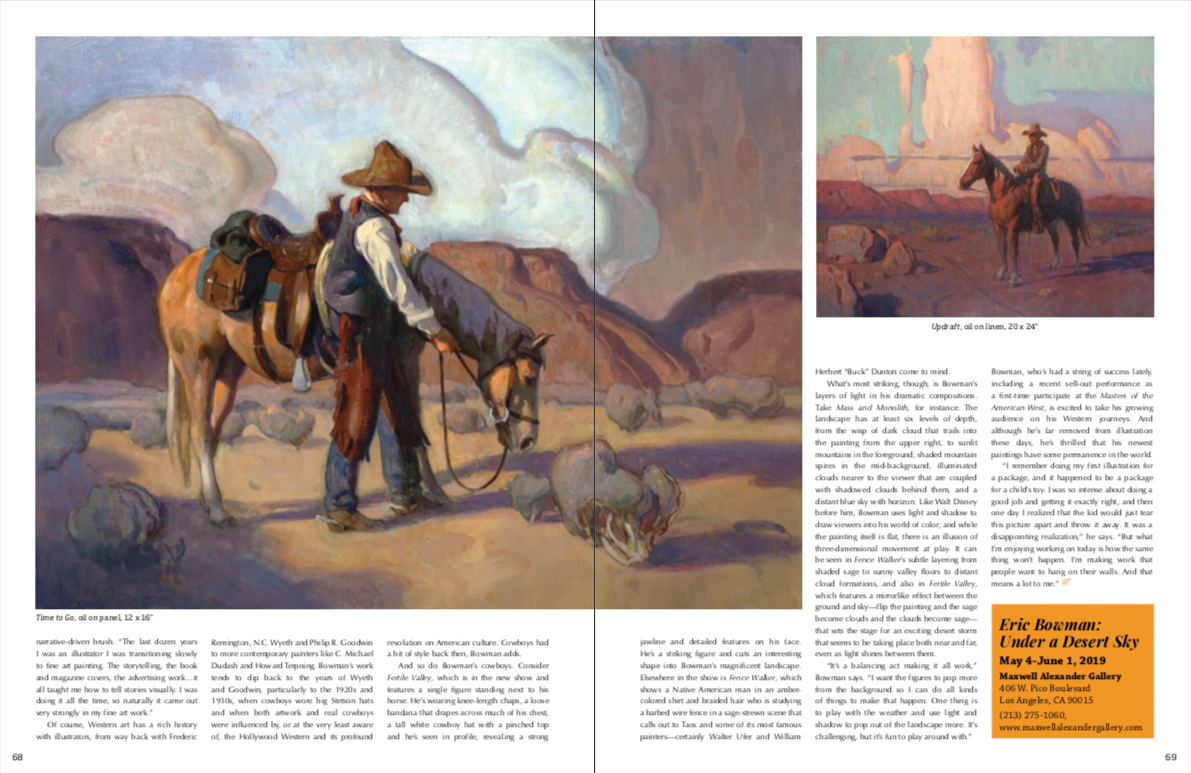

And so do Bowman’s cowboys. Consider Fertile Valley, which is in the new show and features a single figure standing next to his horse. He’s wearing knee-length chaps, a loose bandana that drapes across much of his chest, a tall white cowboy hat with a pinched top and he’s seen in profile, revealing a strong Herbert “Buck” Dunton come to mind.

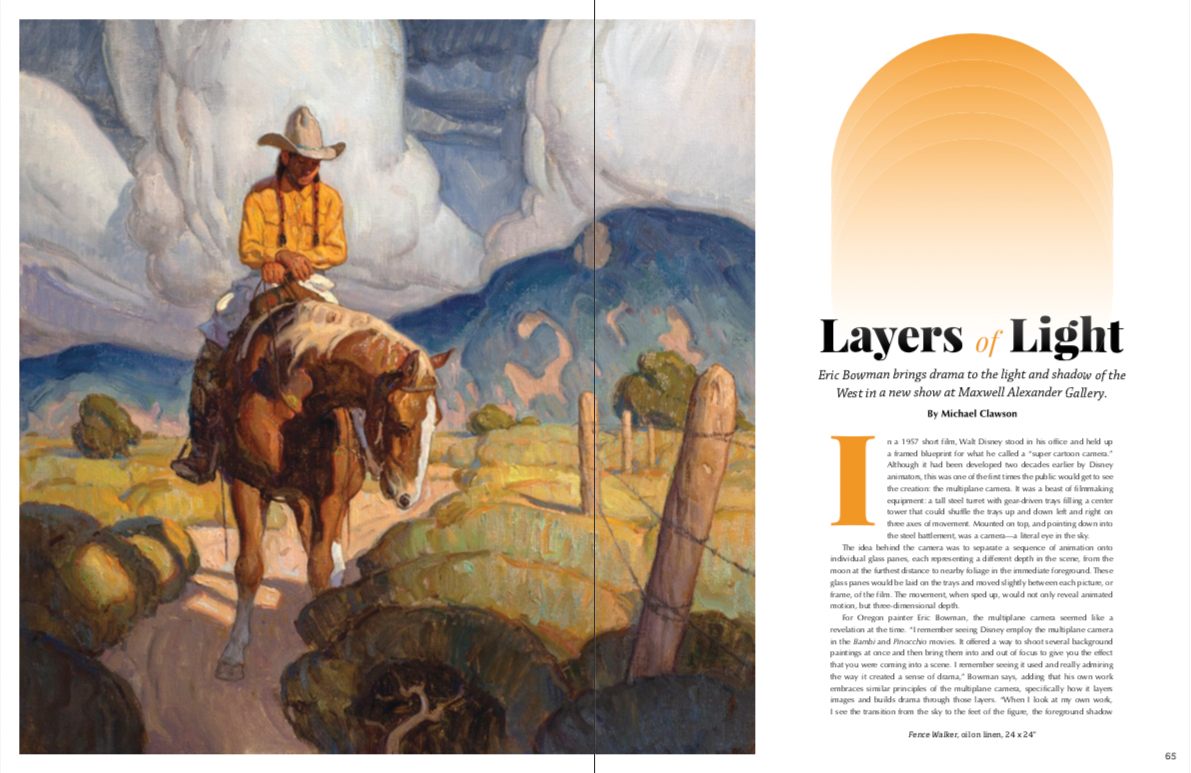

What’s most striking, though, is Bowman’s layers of light in his dramatic compositions. Take Mass and Monolith, for instance. The landscape has at least six levels of depth, from the wisp of dark cloud that trails into the painting from the upper right, to sunlit mountains in the foreground, shaded mountain spires in the mid-background, illuminated clouds nearer to the viewer that are coupled with shadowed clouds behind them, and a distant blue sky with horizon. Like Walt Disney before him, Bowman uses light and shadow to draw viewers into his world of color; and while the painting itself is flat, there is an illusion of three-dimensional movement at play. It can be seen in Fence Walker’s subtle layering from shaded sage to sunny valley floors to distant cloud formations, and also in Fertile Valley, which features a mirrorlike effect between the ground and sky—flip the painting and the sage become clouds and the clouds become sage— that sets the stage for an exciting desert storm that seems to be taking place both near and far, even as light shines between them.

“It’s a balancing act making it all work,” Bowman says. “I want the figures to pop more from the background so I can do all kinds of things to make that happen. One thing is to play with the weather and use light and shadow to pop out of the landscape more. It’s challenging, but it’s fun to play around with.”

Bowman, who’s had a string of success lately, including a recent sell-out performance as a first-time participate at the Masters of the American West, is excited to take his growing audience on his Western journeys. And although he’s far removed from illustration these days, he’s thrilled that his newest paintings have some permanence in the world.

“I remember doing my first illustration for a package, and it happened to be a package for a child’s toy. I was so intense about doing a good job and getting it exactly right, and then one day I realized that the kid would just tear this picture apart and throw it away. It was a disappointing realization,” he says. “But what I’m enjoying working on today is how the same thing won’t happen. I’m making work that people want to hang on their walls. And that means a lot to me.”