The Promise Land

When Jeremy Mann wrapped work on his first feature-length film earlier this year, he immedi- ately recognized the importance of his breakthrough in the medium. “...I will continue to film forever,” he says. “It’s a language which fills my soul with poetry.”

The film, The Conductor, a cerebral and at times surreal journey into an artistic dreamscape—think Lars von Trier or Nicolas Winding Refn, but shot with a painter’s sense of color and composition—allowed Mann to take a four-month hiatus from painting. That break from the easel directly inspired his newest works, on view beginning September 8 at Maxwell Alexander Gallery in Los Angeles. “...I decided to approach the new paintings with an open air of exploration, drawing from my abstract expressionist background, using tried-and-true techniques I learned from my MFA research (i.e., making myself uncomfortable with the materials and techniques to open new windows in this stale, dusty house) and feeding from something I’ve been developing for a long time now, my darkroom prints of Polaroids from homemade cameras.”

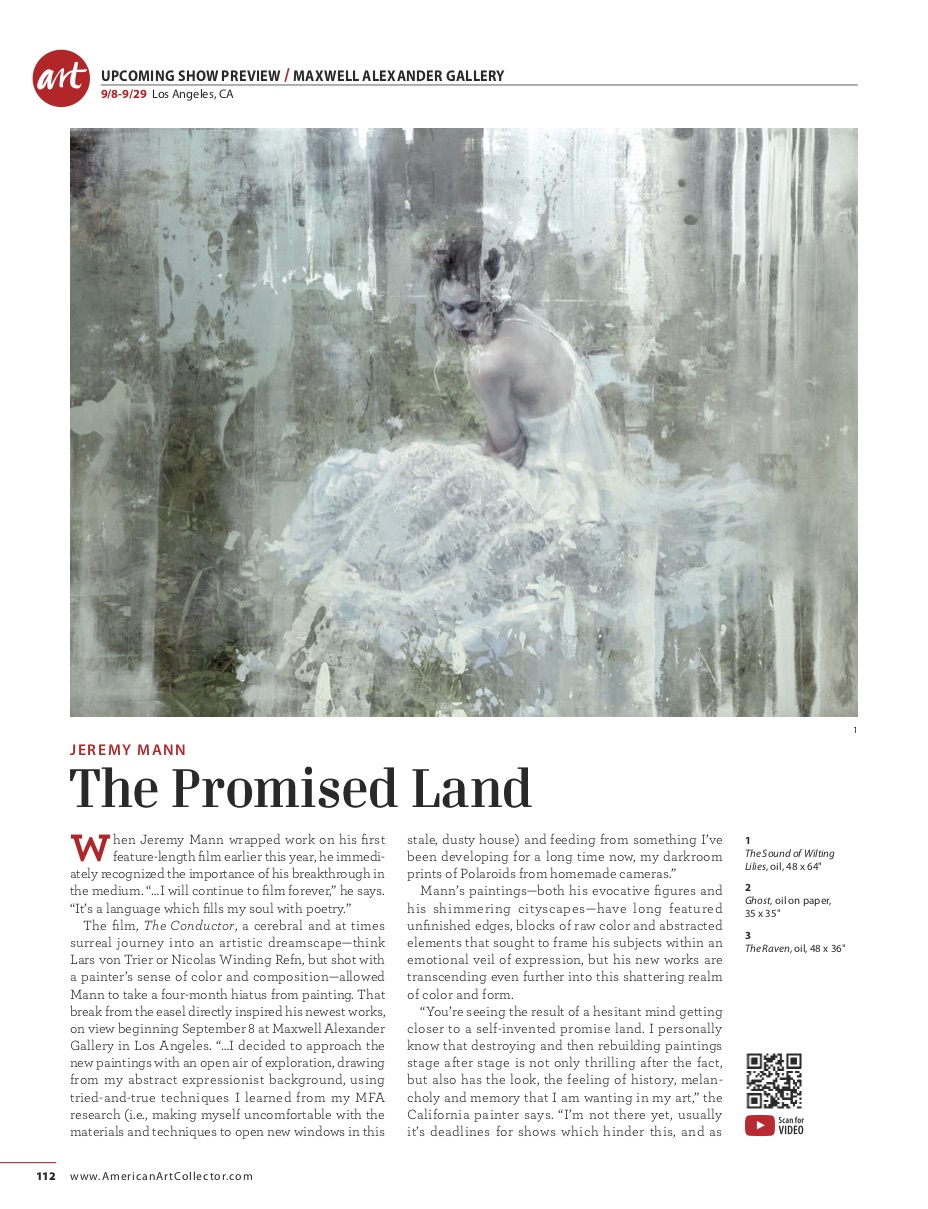

Mann’s paintings—both his evocative figures and his shimmering cityscapes—have long featured unfinished edges, blocks of raw color and abstracted elements that sought to frame his subjects within an emotional veil of expression, but his new works are transcending even further into this shattering realm of color and form.

“You’re seeing the result of a hesitant mind getting closer to a self-invented promise land. I personally know that destroying and then rebuilding paintings stage after stage is not only thrilling after the fact, but also has the look, the feeling of history, melan- choly and memory that I am wanting in my art,” the California painter says. “I’m not there yet, usually it’s deadlines for shows which hinder this, and as you say, you can see it encroaching from the edges of the paintings and reluctant to appear near the focal areas. That’s just reluctance, but it’s like putting cars in space; the point isn’t to have a lot of cars floating in space, that’s useless, the point is to get better technology seeing if we can get such things into space. But people focus on the silly car floating around. So when looking at my paintings now, you could say those abstract expressionist marks and effects are areas of testing ground on final paintings, seeing how it works and reacts to the subject matter, the feeling I want, the mood, while at the same time, experimenting with new materials and techniques, building new tools and trying them out on paintings that I’m afraid to screw up. A big swirling cycle of invention, experimentation, confidence- building, assessment, and then back to invention, keeping the results I want, and perfecting them along the way.

New works include The Sound of Wilting Lilies, featuring a figure calmly sitting in a cascade of white and gray paint that holds her within a tender stillness, a reverence carved into the color. The painting was his first after The Conductor, the hiatus and the building of his photo darkroom. “I went big, knowing that’s what I want, and returned to my earliest years of painting, with a completely rendered underpainting, color toning and then final rendering...every damn leaf, blade of grass, hole in silk,” he says of the piece. “Days later, throw it on the floor and destroy with new tools and techniques, then bring it back to a new life. Almost an allegory for where I am in my life as an artist. I’m not sure that’s necessarily evident in the painting itself, but as every painting, every creation an artist makes, is just one baby step toward the place he wants to be—I feel like this was two baby steps.”

While the new paintings seem to be reaching further into the maelstrom than Mann’s previous works, they are still unequivocally Jeremy Mann paintings, ones that can be identified as his from across a room. “I always tell the story—usually starts at the bar, which is just for some humanism— but the point is that I broke myself away from what I was being taught, what I was seeing around me in the art world, and went off on my own with two important rules: gain wisdom and experiment. Mixing those two goals, an artist will constantly evolve from pushing them-selves to find new ways of saying what they want to say, and then being aware of the effects with the wisdom to decide and choose for yourself which ones you like and which ones you don’t. Then, just do the ones you like perfectly (that part has all the hard work in it). The great thing about this process is that I am making the judgement call, [without] confusion about ‘what sells,’ ‘will I get likes,’ ‘will other artists like this.’ Those ideas are poison, ridiculous to even enter the mind, and it makes me sick how prevalent they are becoming in artists of all stages. That is why you can identify my artwork sepa- rate from any other, infused with other inspirations, but evolved to be my own, and across any medium. Having the self- respect to be true to yourself, this is the fundamental reasoning and goal in every workshop I teach—to be you, not me. It’s already difficult to be me, it’s easy to be yourself.